Indy star: From breakrooms to living rooms: Office conversions fuel downtown housing boom

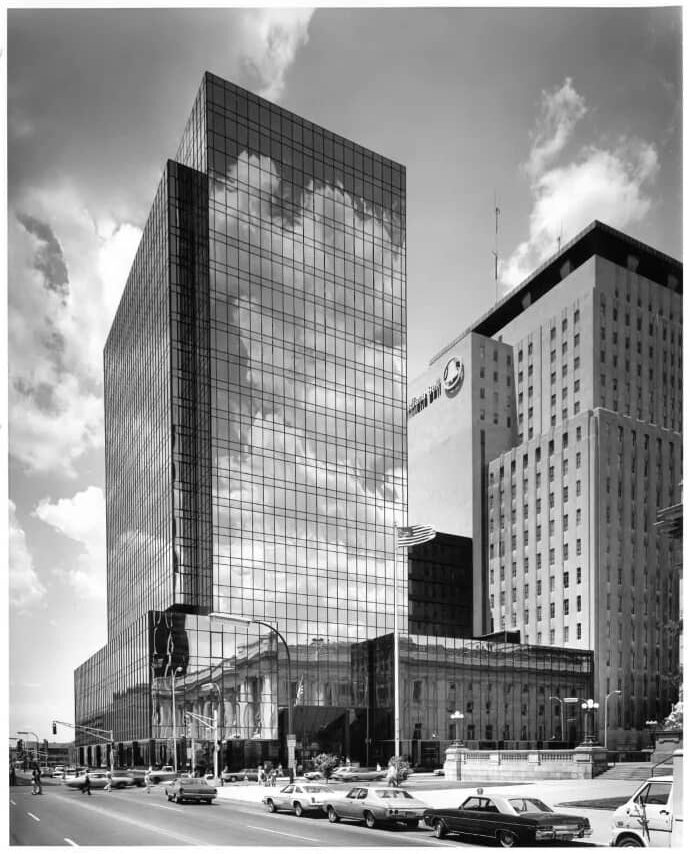

From the outside, 220 N. Meridian looks almost the same today as in 1974 when the building opened. Inside, however, it’s a different story.

Historic photos of the former AT&T building show offices filled with stacks of papers and filing cabinets. Bright orange cafeteria chairs speak to a different time, when workers fueled the downtown economy with energy.

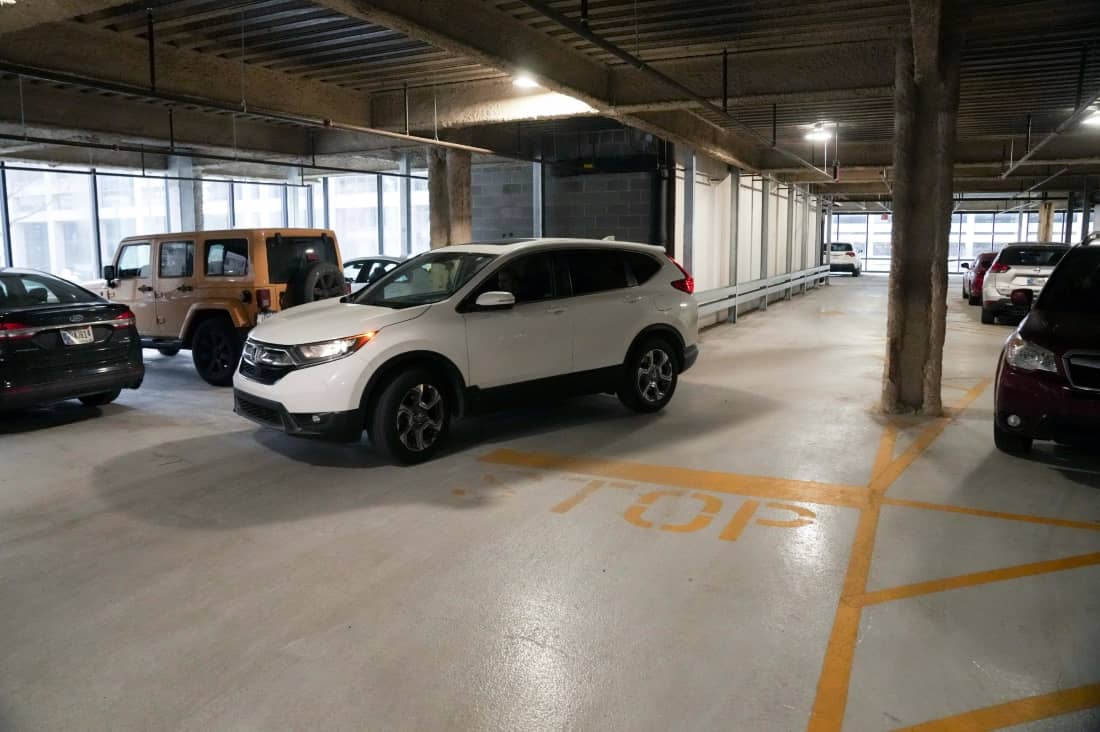

A small fraction of AT&T employees still work in the building on the top three floors, but they will officially move out this summer, marking the end of a 51-year chapter. The move will allow the Keystone Group to finish a $110 million redevelopment project it started in 2020 after buying the building two years prior. Now, the building features high-end apartments, along with an 11th-floor outdoor pool deck and three-story indoor parking garage.

Now, the building features high-end apartments, along with an 11th-floor outdoor pool deck and three-story indoor parking garage.

The story of 220 N. Meridian, the first project in central Indiana to convert offices into residences, represents a larger shift in how developers today view properties in downtown Indianapolis and across the country. Adaptive reuse projects, or building conversions, are becoming increasingly more popular as demand for urban office space and apartments flip-flops.

This year, Indianapolis looks to gain an additional nearly 600 apartments in former office buildings, including:

- 220 N. Meridian, former AT&T building: 51 apartments in the pipeline by Keystone Group, adding on to 216 units it finished in the building in 2023.

- Gold Building, formerly housed public county defender offices: 354 apartments in the pipeline by Gershman Partners and Citimark.

- 130 E. Washington St., former home of Angie’s List: 180 apartments in the pipeline by Holladay Properties.

Office-to-apartment conversions are picking up steam nationwide as the commercial office market lags and people rent for longer. In the Indianapolis metro area, millennials are flocking to downtown, increasing the demand for housing there.

These conversion projects aim to capitalize on that.

“It’s important to make sure we have a strong city core, not just for the city of Indianapolis, but this is the state capital,” said Ersal Ozdemir, Keystone Group founder. “So we feel like it’s important to continue to have a focus and invest in our core.”

A photo of the tower at 220 N. Meridian in the 1970s in downtown Indianapolis. The office building opened in 1974 and housed the AT&T headquarters. Provided/Keystone Group

Across the country, about 70,000 apartment units are in the pipeline to be converted from desk to living space this year — representing almost 42% of adaptive reuse projects, according to a data report published in February by RentCafe, an apartment research firm website. The rise in adaptive reuse projects began a few years before the pandemic as developers began to look at existing vacant office space rather than empty land for new homes.

Since 2010, housing supply has fallen short of fulfilling demand, and in 2018, large investment firms saw the opportunity to add rental properties to their portfolios, said Doug Ressler, manager of business intelligence at commercial real estate research firm Yardi Matrix based in Phoenix. In downtown Indianapolis, developers were seeking to take advantage of empty historic buildings.

“It was already happening, but then the pandemic accelerated it,” said Bill Browne, president of the Indianapolis Historic Preservation Commission and part of the design team for the Bottleworks District renovation.

Long interested in historic preservation, Keystone converted a building at 141 S. Meridian St. into condominiums more than 20 years ago. More recently, Keystone renovated the company’s office headquarters on Pennsylvania Street and converted the Illinois Building into the InterContinental Hotel, whose doors opened last month.

The 220 project “felt like the next step in creating a strong urban core,” Ozdemir said.

What makes a good office-to-apartment conversion

Market conditions – including high interest rates, increasing construction costs and low asking prices for office buildings – are also pushing developers to consider more adaptive reuse projects. In today’s economy, retrofitting old buildings can be more cost effective than constructing new ones.

A building at 130 East Washington Street is pictured Tuesday, March 25, 2025, in downtown Indianapolis. Christine Tannous/IndyStar

Like most development projects, the right fit for a building’s use depends on the individual property. However, with apartment conversions, several factors are seen as necessary.

“Not every building is fit for adaptive reuse. If it’s bigger than 50,000 square feet, a wide property, where the stairwells are located, where the windows are lined — they all play a role and it depends building to building,” said Rachel Patten, a Colliers senior associate in Indianapolis.

The building must have a floor plan adaptable to residential units, easy access points, a good location and preferably, options for parking, developers and commercial real estate experts say.

“Older buildings sometimes represent a better adaptability because they have high ceilings and good floor plans,” Ressler said.

After looking for an apartment conversion building for some time, Holladay Properties, a South-Bend developer, recently announced a project to convert the 12-story building at 130 E. Washington St. into as many as 180 apartments. The $40 million price tag to redevelop the site, which will be called Pembroke Place, is far less than a new build would cost, said vice president of development Jordan Corbin.

Federal historic tax credits and a $4.2 million 10-year tax abatement from the city further cemented the project as a financial fit for Holladay.

“What we can buy that building for compared to what you can build it for is very attractive, and there’s all of those incentives. We wouldn’t even come close to making a ground-up development work without all these incentives,” Corbin said. “Development always comes back to the numbers.”

What’s next for the downtown market

As residential space becomes more limited downtown and office buildings empty, adaptive reuse projects may become more common and financially sound undertakings for developers. Roughly 13% — or 13.9 million square feet — of Indianapolis office space is suitable for conversion, according to Yardi Matrix data.

City officials do all they can to financially support adaptive reuse projects. For the three largest conversion projects underway, the Department of Metropolitan Development committed at least $35 million in tax savings and incentives.

Bringing more housing downtown is a priority for the city under the Downtown Resiliency plan, said department director Megan Vukusich.

The incentives typically require a certain number of units to be earmarked as affordable or workforce housing and can include public art requirements as well.

At the Gold Building on Ohio Street, an $185 million office-to-apartment conversion is part of a block-wide redevelopment of the City Market Plaza, a former center for foot traffic downtown.

The city can use land as another incentive for developers to take over dilapidated or underutilized properties, Vukusich said. On the east end of downtown, the city leveraged its ownership of the Cole Motor campus to strike a deal with 1820 Ventures, offering to sell the real estate developer the land in return for a planned 200-unit apartment project.

Such projects take some heat off the commercial real estate market, which has been struggling with high vacancy rates since the pandemic. In a recent report, JLL reported an increase in office occupancy for the first time since 2018 in part because of a drop in market supply.

“We hope we are doing our part by taking these older office buildings off the market,” Corbin said.

Looking around Indianapolis, Browne said he can think of a few strong candidates for full or partial apartment conversions, like the OneAmerica tower that already has separate elevator banks or the Regions tower, which went into foreclosure last year.

Ultimately, partially empty buildings aren’t particularly attractive to anyone, he said.

“It’s better to do something rather than nothing,” Browne said. “And I think there’s enough understanding that the office market will not come back like we thought.”